Black Lives and Black Beauty

LESSON ONE

Key themes

Beauty, Identity, Bias

Participants will study how beauty standards influence social assimilation and how coded language can be used to show bias.

Objectives

At the end of this lesson, participants will be able to:

- Define terms such as Black aesthetic and coded language

- Identify internalized structures of oppression

- Discover evidence of bias

Image Courtesy of Colin In Black & White

Key themes

Beauty, Identity, Bias

Participants will study how beauty standards influence social assimilation and how coded language can be used to show bias.

Objectives

At the end of this lesson, participants will be able to:

- Define terms such as Black aesthetic and coded language

- Identify internalized structures of oppression

- Discover evidence of bias

Image Courtesy of Colin In Black & White

LESSON ONE

Introduction

Black Lives and Black Beauty

Do you know how headwraps in the Black community came to be? In the eighteenth century, Black women (particularly free mixed-race women) in New Orleans wore elaborate hairstyles and hair accoutrements. In response to this attention-drawing practice, a law was enacted that prohibited free Black women from displaying ‘excessive attention to dress’ (hair included) in the streets of New Orleans. This was called the “Tignon Law” and it required free Black women to publicly dress similarly to enslaved women by covering their heads with scarves. In an act of defiance, the women of the time took what was meant to be an oppressive law and eventually turned it into a fashion statement, accessorizing their head wraps with jewelry, hats and feathers.

In this lesson, let’s examine the aesthetic of Blackness – both as a tool of resistance and expected identity.

”The public display of hairstyles by women of color was outlawed in 1785. Women of the time, being familiar with the African head wrap (a gele), used the new restriction as an opportunity to further their stature by using beautiful fabrics and intricately wrapping their hair. Ironically, the law designed to detract attention from the beauty of these women had the opposite results.” Terry Flucker, historian and author of “African Americans of New Orleans.”

1837 portrait by François (Franz) Fleischbein of his housekeeper Betsy, a free woman of color, living in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Source: Portrait of a Free woman of Color, the Historic New Orleans Collection, 1985.212

LESSON ONE

Introduction

Black Lives and Black Beauty

Do you know how headwraps in the Black community came to be? In the eighteenth century, Black women (particularly free mixed-race women) in New Orleans wore elaborate hairstyles and hair accoutrements. In response to this attention-drawing practice, a law was enacted that prohibited free Black women from displaying ‘excessive attention to dress’ (hair included) in the streets of New Orleans. This was called the “Tignon Law” and it required free Black women to publicly dress similarly to enslaved women by covering their heads with scarves. In an act of defiance, the women of the time took what was meant to be an oppressive law and eventually turned it into a fashion statement, accessorizing their head wraps with jewelry, hats and feathers.

In this lesson, let’s examine the aesthetic of Blackness – both as a tool of resistance and expected identity.

Click image for more information

”The public display of hairstyles by women of color was outlawed in 1785. Women of the time, being familiar with the African head wrap (a gele), used the new restriction as an opportunity to further their stature by using beautiful fabrics and intricately wrapping their hair. Ironically, the law designed to detract attention from the beauty of these women had the opposite results.” Terry Flucker, historian and author of “African Americans of New Orleans.”

1837 portrait by François (Franz) Fleischbein of his housekeeper Betsy, a free woman of color, living in New Orleans, Louisiana. Source: Portrait of a Free woman of Color, the Historic New Orleans Collection, 1985.212

HairStory and History

What is it about hair?

In Colin in Black and White, Colin confronted the tension between hair conformity and hair expression when he cut his cornrows to wear a shorter, more “acceptable” hairstyle. According to scholar Dr. Tina Opie, “Viewers witnessed how traumatizing this “cultural cutting” was for Colin. His cornrows signified his personal quest to more deeply connect with his Black roots. Yet, the white power structure was uncomfortable with his hairstyle, therefore, Colin’s cornrows were denigrated and deemed unacceptable. Similar anti-Black attitudes have been, and are still, reflected in organizational appearance policies that prohibit Afrocentric hairstyles.”

Black people have worn various hairstyles for centuries. From afros to hot-ironed straight hair, twists, locs, chemically straightened hair, wigs, braids and weaves, hair has been seen not only as a sign of beauty and self expression, but often as a form of resistance.

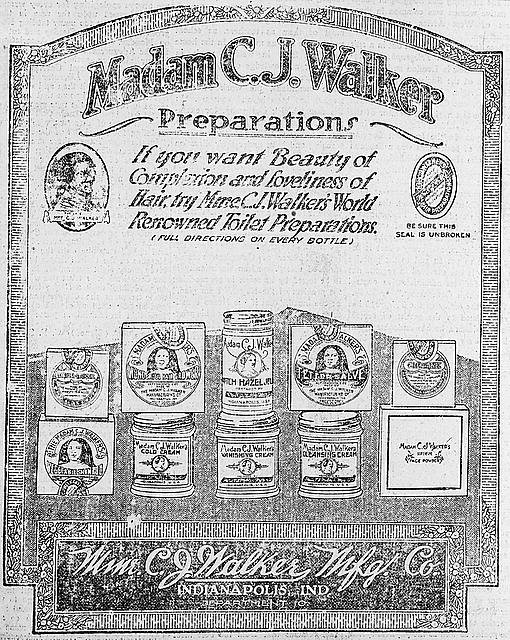

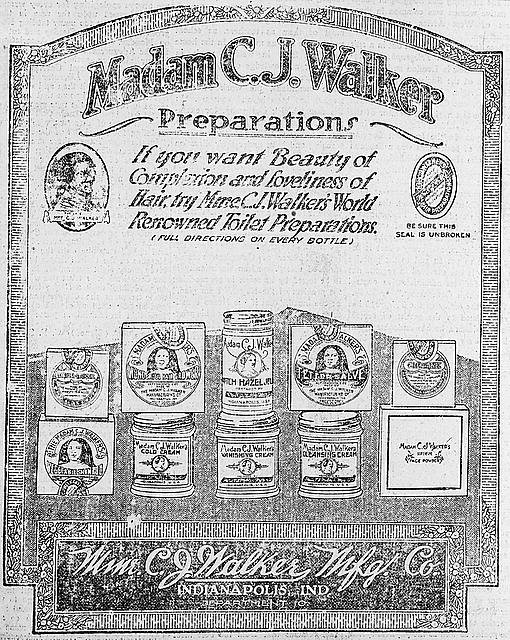

A 1920 advertisement for beauty products from the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Source: Library of Congress

A 1920 advertisement for beauty products from the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Source: Library of CongressWhen Africans were enslaved and taken to new lands against their will, one way to connect with one’s homeland, social status, marital status and even religion, was through one’s hairstyle. In acts of defiance, enslaved African women carried seeds in their hair as they were bought and transported from their homelands to other parts of the world. Written accounts and oral traditions confirm this claim.

By the late nineteenth century, straightened hair was gaining popularity. Many Black women began straightening their hair in order to assimilate to a white standard of beauty and respectability. Others had no choice but to straighten their coils, as their employers refused to employ them if they didn’t.

Chemist, inventor and philanthropist Annie Turnbo Malone and entrepreneur Madame C.J. Walker facilitated new options for Black women’s hair care. Both women became multi-millionaires by offering products that involved scalp preparation, lotions and iron combs, promising Black women hair that was easier to manage and maintain.

Today, the hair care industry is a 77 billion dollar enterprise worldwide and it continues to grow daily.

“Black people continue to navigate how they present themselves at work. Hair is a particularly precarious consideration,” says Dr. Opie. “Wearing natural or Afrocentric hairstyles may be interpreted as more dominant and less professional. Yet, if Black people authentically desire to don Afrocentric hairstyles, the suppression of this expression may hamper Black people’s well-being and negatively impact work engagement. Organizations may benefit from interrogating their workplace norms for cultural biases that unnecessarily penalize Afrocentric hairstyles. Focusing on task-related performance rather than policing Black people’s hair may yield organizational benefits.”

HairStory and History

What is it about hair?

In Colin in Black and White, Colin confronted the tension between hair conformity and hair expression when he cut his cornrows to wear a shorter, more “acceptable” hairstyle. According to scholar Dr. Tina Opie, “Viewers witnessed how traumatizing this “cultural cutting” was for Colin. His cornrows signified his personal quest to more deeply connect with his Black roots. Yet, the white power structure was uncomfortable with his hairstyle, therefore, Colin’s cornrows were denigrated and deemed unacceptable. Similar anti-Black attitudes have been, and are still, reflected in organizational appearance policies that prohibit Afrocentric hairstyles.”

Black people have worn various hairstyles for centuries. From afros to hot-ironed straight hair, twists, locs, chemically straightened hair, wigs, braids and weaves, hair has been seen not only as a sign of beauty and self expression, but often as a form of resistance.

A 1920 advertisement for beauty products from the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Source: Library of Congress

A 1920 advertisement for beauty products from the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Source: Library of CongressWhen Africans were enslaved and taken to new lands against their will, one way to connect with one’s homeland, social status, marital status and even religion, was through one’s hairstyle. In acts of defiance, enslaved African women carried seeds in their hair as they were bought and transported from their homelands to other parts of the world. Written accounts and oral traditions confirm this claim.

By the late nineteenth century, straightened hair was gaining popularity. Many Black women began straightening their hair in order to assimilate to a white standard of beauty and respectability. Others had no choice but to straighten their coils, as their employers refused to employ them if they didn’t.

Chemist, inventor and philanthropist Annie Turnbo Malone and entrepreneur Madame C.J. Walker facilitated new options for Black women’s hair care. Both women became multi-millionaires by offering products that involved scalp preparation, lotions and iron combs, promising Black women hair that was easier to manage and maintain.

Today, the hair care industry is a 77 billion dollar enterprise worldwide and it continues to grow daily.

“Black people continue to navigate how they present themselves at work. Hair is a particularly precarious consideration,” says Dr. Opie. “Wearing natural or Afrocentric hairstyles may be interpreted as more dominant and less professional. Yet, if Black people authentically desire to don Afrocentric hairstyles, the suppression of this expression may hamper Black people’s well-being and negatively impact work engagement. Organizations may benefit from interrogating their workplace norms for cultural biases that unnecessarily penalize Afrocentric hairstyles. Focusing on task-related performance rather than policing Black people’s hair may yield organizational benefits.”

LESSON ONE

Activity I: HairStory

Procedure

Let’s explore the history of policing Black hair as a way of controlling the Black aesthetic.

BEGIN: by watching a scene from episode one of Colin In Black & White. In this episode Colin is excited to have his hair braided for the very first time. His mom and other adults in his life were not as supportive. Who/What made Colin try such a ‘bold’ hairstyle? Watch this clip to find out.

EXAMINE: The Crown Act website. The state of California was the first to pass the Crown Act in 2019. Because of this law, workers who wore braids, locks, and twists could not be discriminated against because of their choice of hairstyle.

ANSWER: the reflection questions in the next section.

LESSON ONE

Activity I: Reflection Questions

- 1 | How is hair discussed in your community? In your school? In your family?

- 2 | What type of hair is centered? What type of hair is marginalized?

- 3 | Has there ever been a time when your hair prohibited you from participating in an activity? What was the activity?

- 4 | Besides Black hair, do you know of other beauty aesthetics that are marginalized in your community?

- 5 | Should your employer be able to decide which hairstyles are “appropriate” for the workplace?

- 6 | Only a handful of states have been able to pass Crown Acts. Several states have failed and there is no federal law protecting your right to wear locks, knots, braids and twists (only afros). Why do you believe the federal government is hesitant about passing a new law that prevents all hair discrimination?

Air Jordans, Gold Chains and Coded Language

“Disrespectful” “race baiter” and “treasonous” were harmful and hateful words used by critics to describe Colin Kaepernick’s peaceful social justice protest against police brutality, which began in 2016.

From the media to the average sports fan, everyone seemed to have something to say about his actions. Often times the language was outright mean and many times it was racist. But sometimes, it was coded.

Coded language unfairly uses negative and inflammatory words to incite backlash. When those unhappy with his protest called him “un-American” or “traitor,” they were using coded language.

Coded language allows people to redefine the meanings assigned to certain words, based on one perspective as opposed to what the word really means. The words can then be used as weapons. If you are not listening closely, you take them as truth without investigating. Coded language allows you to use words that have layers of meaning without being specific.

Coded language often reveals a bias in its users and can result in racial inequity.

“Bias is such a tricky concept to teach,” explains Dr. Kristina Poznan, Managing Editor at The Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation. “One thing that I always want students to come away with is an understanding that bias is about perspective (which can often mean racial prejudice), but that the word bias itself does not automatically mean prejudice. So, for example, a news source on a foreign conflict will often be biased toward an American perspective, even if they aren’t reporting on the conflict utilizing prejudicial language about the combatants.”

Air Jordans, Gold Chains and Coded Language

“Disrespectful” “race baiter” and “treasonous” were harmful and hateful words used by critics to describe Colin Kaepernick’s peaceful social justice protest against police brutality, which began in 2016.

From the media to the average sports fan, everyone seemed to have something to say about his actions. Often times the language was outright mean and many times it was racist. But sometimes, it was coded.

Coded language unfairly uses negative and inflammatory words to incite backlash. When those unhappy with his protest called him “un-American” or “traitor,” they were using coded language.

Coded language allows people to redefine the meanings assigned to certain words, based on one perspective as opposed to what the word really means. The words can then be used as weapons. If you are not listening closely, you take them as truth without investigating. Coded language allows you to use words that have layers of meaning without being specific.

Coded language often reveals a bias in its users and can result in racial inequity.

“Bias is such a tricky concept to teach,” explains Dr. Kristina Poznan, Managing Editor at The Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation. “One thing that I always want students to come away with is an understanding that bias is about perspective (which can often mean racial prejudice), but that the word bias itself does not automatically mean prejudice. So, for example, a news source on a foreign conflict will often be biased toward an American perspective, even if they aren’t reporting on the conflict utilizing prejudicial language about the combatants.”

Unprofessional

Athletes like Colin, at the highest level of their careers, have often been on the front lines of controversy, whether it’s political issues or pop culture. Players have endured penalties and sometimes monetary fines for choosing to speak out about their beliefs, for dressing in ways that made them comfortable and even for how they groom themselves.

Colin in Black and White examines how the sports world received basketball players like Allen Iverson, who was one of the first NBA players to wear cornrows. Did you know that the National Basketball Association also once considered baggy clothes, sunglasses and gold chains unprofessional attire? Between 2000 and 2005, the NBA fined over 20 players $10,000 each for wearing baggy shorts. In 2005, the NBA levied an all-out ban on gold chains, sleeveless shirts, sunglasses, baggy clothes and other items deemed unprofessional. This rule prompted player Jason Richardson to respond, “Just because you dress a certain way doesn’t mean you’re that way. Hey, a guy could come in with baggy jeans, a durag and have a PhD, and a person who comes in with a suit could be a three-time felon.”

It was apparent that the word “unprofessional” was coded language for “Black” and a bias against hip hop culture.

LESSON ONE

Activity II: So Articulate: A Bias Decoding Activity

Coded language has long been a tool of oppression used to share thinly veiled racist sentiments in socially acceptable ways. In the next activity, participants will discover evidence of this practice in printed and visual text.

Coded language has long been a tool of oppression used to share thinly veiled racist sentiments in socially acceptable ways. In the next activity, participants will discover evidence of this practice in printed and visual text.

Procedure

BEGIN: by watching a clip from Colin In Black & White.

READ: ‘Crafty’ Vs. ‘Sneaky’: How Racial Bias In Sports Broadcasting Hurts Everyone.

INVESTIGATE: biases. Click on this link to view a gallery of images. Based on what you see, what story do you think each image is telling?

SHARE: this group of images with a classmate or family member. Did you and the person you shared the images with have the same responses?

ANSWER: the reflection questions below.

LESSON ONE

Activity II: Reflection Questions

- 1 | When was a time when you heard someone describe another person based on their race or ethnicity? Was the description accurate?

- 2 | How do we determine what is valuable (crafty vs sneaky) and who gets to make that determination?

- 3 | The NBA used the term unprofessional to describe the way some of their players dressed, so did Colin’s dad in the clip. How is the word being used as coded language? What does it really mean?

- 4 | There are lots of conversations about race, ethnicity and fairness these days. Who do you believe often gets left out of these conversations?